The Name Of The Light

And Dreams Of Trees

Highway 26 runs like a vein between Portland, Oregon and the coastal town of Seaside, seventy-nine miles due west. Once you escape city limits, the road dwindles to two lanes that first cut across rolling hills of farmland and then head through the middle of forest thick with Douglas fir. You, in your little car, can feel like an intruder crawling over the feet of the forest that tower on either side of the road. It’s dark and quiet and feels like you’re driving through the middle of a secret.

This stretch of road is where I used to let my worried and jagged thoughts escape out the window. I didn’t do this on purpose necessarily, but there’s something about those trees that made me trade in my busy brain—the way they stood together, the gentle tangle of light and dark, the way the air smelled sweeter there, how they bent with the wind, the feeling of peace that permeated.

It used to be that you’d see clearcuts in the distance—areas in tidy, geometric shapes with trees that are logged and cut to the ground. For most of the decade that I lived in Oregon, the clearcuts still felt far off, and therefore somehow less important. But one Sunday on a drive to the beach I was in roadtrip position with my head resting back on the headrest, arms hanging limp at my sides, and my eyes in a dreamy scan of the forest when a clearcut popped into view just feet from the road. Behind a thin, peek-a-boo curtain of a few trees left standing, the stubble of hacked tree trunks and leftover branches marred the ground.

The forest is not mine—and I know this. But this clearcut felt brazen, like the sudden appearance of a burglar in my bedroom. It crept up on me, and I couldn’t figure out how it had gotten so close without my noticing.

This is when my then-four-year-old daughter piped up from the backseat. “Why do the hills look so sick?” she asked. And it’s true. They did look sick.

I heard myself tell her something about needing trees for houses and floors and furniture, which is also true. But this was no answer. It was information. It did nothing to explain why the hills looked sick or appease the queasy feeling that precious secrets were being stolen from right under my nose or quell the sense that I was somehow just letting it happen.

It was around this time that I had a dream. In the dream I am standing in a forest under an inky dark sky. An oak tree looms before me with thick, snaking branches that kink and bend and grow right before my eyes. Light glows from the tiny tips of each branch. The whole tree radiates in the darkness. I bask in the luminosity and have a nagging feeling that there is something I need to do or know. I’ve had this dream before. It is my job, I think, to name the light. I don’t know how I know that I am meant to name the light or what will happen when I do. Wheels will be set in motion perhaps. Or something important will shift. The problem is that for the life of me I can’t remember the name. The light knows I know its name, as does the entire forest. Everything waits as I stand before the tree and search my memory. The name is on the tip of my tongue. I feel it coming. I’m about to speak it when I hear a voice.

“Mama, Mama.” This throws me. I’m distracted. I hear it again, “Mama!”

I bolt upright in bed. My daughter is calling from her room across the hall. I stumble out of bed in a fog of waking worry over what has her yelling. My feet shuffle themselves to her door as the rest of me tries to stay deep within my dream, desperate to remember and then speak the name of the light, wondering what epic event will happen when I do.

My daughter is cozy under her covers. “Mama,” she says. “My feet are cold.”

It’s like she’s speaking in a foreign language. “Your feet are cold?”

“Can you get me some socks?”

“Socks.” I repeat. Socks and the name of the light.

I fumble in the dark for something to warm her toes. The cosmic timing is a joke, but I shove the wondering about the “why” of it from my mind and fight to keep hold of the thin thread of dream that just might connect me to the name of light.

I feel around in the dark for socks and then her bed and then her little kid feet. I slide the socks on, kiss the warm soft of her forehead, and make my way back to bed. By the time my head hits the pillow, the dream is gone.

But my dream and the clearcut forest along Highway 26 stay with me like an imprint on a photographic negative. Their absence had a presence, and it haunted me. I had to do something. But what? I signed up for Urban Forestry 101 with Portland’s Department of Urban Forests. I read everything about I could about trees. At the time, Professor Suzanne Simard of the Department of Forestry at the University of British Columbia had just discovered that trees communicate with each other through their root systems. If a tree has a disease, for example, it sends chemical signals to other trees alerting them to the threat. These trees then adjust their chemistry to protect themselves.

I also learned how redwood trees are astoundingly resilient. My favorite fact is that when a redwood tree dies, its own roots give birth to new trees in a circle around where it once stood. These circles of new growth are called Family Circles, and you can see them all over redwood forests. It’s an impressive survival mechanism to be sure. But, I wondered, can’t we learn something from this particular form of survival? Do we come together when something we know and love comes to end? Or do we draw lines in the sand to separate “us” from “them” and protect what’s “ours?”

Another fact was striking: one-tenth of 1 percent of all the seeds that fall from a Douglas fir actually take hold. The rest are blown away, eaten by birds, waterlogged, or succumb to some other bigger force.

While a fact like that could make you feel cynical, somehow it gave me an incredible sense of hope. All those seeds that a tree generates feel like so many possibilities, so many chances to be. And when I looked around and saw how many trees actually do make it, all it takes for trees to survive, and then, even more, what they do for us—make the oxygen that we breathe, for one—it seems impossible that I never worry if there is enough oxygen.

And yet, there it is: I breathe. And I write.

All of this research inspired a novel. My teenaged protagonist, Jade, took walks in old-growth groves and leaned back against the trunks of trees. She absorbed gems of wisdom, as if the trees shared information with her as they do with each other through their root systems. The wisdom was like a generous gift. Jade wrote what she learned on small tags and then tied the tags to trees so that others would read them and also come to know the voice of trees.

I became secretly jealous of Jade’s tree tagging adventures. I wanted to tag trees, too. So I got in touch with a dear friend. Tracy Schlapp is a designer who runs a small print shop called Cumbersome Multiples out of a garage in her backyard. She helped me create a tree tagging kit that included small rectangles of recycled chipboard, twine, and a field guide with a collection of tree facts and wise sayings about interconnection. We called our project Tree Dreams.

On my first tree tag I wrote, Trees use sunshine to make the air that you breathe. What secret magic do you make and then give away? On the next tag, inspired by the ways that trees give and take from everything around them, and concerned about our propensity to think of trees as an endless resource, I wrote, Nothing works if there is only taking. And then I went tagging.

At first I felt like a crazy lady tying messages to tree branches. I also worried that I would get caught, though caught doing what I wasn’t entirely sure. I wasn’t committing a crime that I was aware of. We’d taken care to use material that would dissolve safely back into the earth. So I took the twine between my fingers, said Hello! to the tree that I was asking for the favor of adorning with a tag, and tied the tag loosely around a thin branch where it dangled in the breeze.

Tracy and I created more Tree Dreams kits and asked others if they would tag trees, too. To our surprise, many said yes. Pretty soon Tree Dreams tags were hanging around the world and across the United States. We we awarded a grant to adapt Tree Dreams for the classroom. We created curriculums and supported teachers around the country. Most recently, Tree Dreams went on tour with the Tree Circus, which teaches kids of all ages about the power and wonder of our arboreal friends.

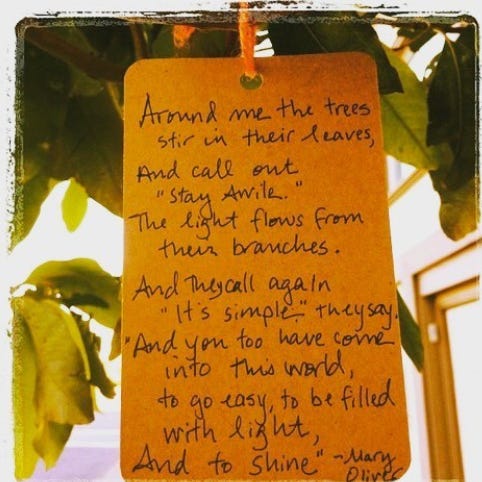

Throughout all of this I continued to make it my practice to tag trees with the dreams that meant the most to me. One day I was preparing a tree tag to hang during one of my tree tagging adventures. I wrote a quote from the great Mary Oliver from her poem When I Am Among the Trees. I wanted to include wisdom from the second half of the poem: Around me the trees stir in their leaves/ And call out, “Stay awhile.”/ The light flows from their branches./ And they call again, “It’s simple,” they say,/ “and you too have come/ into this world to do this, to go easy, to be filled/ with light, and to shine.”

As I wrote those words I immediately felt their meaning. My dream of the glowing tree and my need to name the light came flooding back. It finally dawned on me as if I’d known it all along but now could suddenly see: The name of the light was no name at all. There was nothing name. There was only something to be.

I am happy to share Write Your World Awake freely and your support really makes a difference. When you like, share, comment, or restack my work gains exposure and a greater readership. Thank you for helping to make that happen!

I’d love to know: What is calling to you to be in the world? Is it something to do, or something to be? What are you doing to make that happen?

We’re all in this together and we have so much to learn from each other. So please take a moment and share your wisdom!

You can find my design partner, Tracy Schlapp, on Substack at The Pony Express, where she writes about her work in Oregon Prisons, where they Tree Dream, too.

I love it